Back to

the Ellis Family Homepage

The

Supper of the Lord at Corinth

1

Corinthians 11:17-34

The Lord’s Supper in Corinth has

been a source of many questions as far back as the days of Paul. Ever since the very institution of the

supper by the Lord Jesus, there have been questions about the spiritual and

moral implications of such a memorial feast.

My purpose is to expose 1

Corinthians 11:17-34 and take a fresh look at the views about the meaning of

the passage, making the proper application for ourselves. What is Paul doing in this passage of

scripture? Is he simply re-instituting

the Lord’s Supper, and if he is, why was this necessary? What is the cultural context of the

Corinthian church and their participation in the supper? Why does Paul address the church in Corinth using such strange terms, that we don't seem to see today in the supper? All of these questions are things that we

will attempt to answer in this paper.

It is important also to note that while the term “eucharist” is not a

scriptural term for the bread and cup or the supper of the Lord, it is, however, clearly shaped as that

supper whose meaning is to “give thanks" or "thankfulness;” for which we also are thankful.[1]

It is interesting to note the practice of so many churches in their observance of the Lord’s Supper. Without asking why, very often congregations come to that special time in the service, and after a song to “prepare our minds” we gather around a table to partake of the bread and fruit of the vine. The men gather around the table while facing the crowded pews before them, and often make the adjustments to stand just so – to be symmetrical with the other men passing out the trays to the audience.

In a meeting of the saints at one

location, LaGard Smith relates a story about the Lord’s Supper and its present

day application. “With one swift punch

of the finger into the middle of the large flat wafer, the whole “loaf”

instantly became two distinct pieces… with another quick pinch of the wafer,

our sister… [was] apparently assured that, by her hand, the scriptural mode of

partaking the Lord’s Supper had narrowly escaped desecration.”[2]

The proper form and function is necessary with any

act of worship to God, as it was in the days of the temple worship. Is our exact form and function required to be the same today as theirs in the early church 'in all things?' Or is the theological meaning behind the act of worship what counts? Is it both restoration of form and correct theological application of function? Probably so, but how do we apply the teaching of Paul to our modern day when the

instruction was intended for a specific

incident in first century Corinth?

How can we improve our practice of observing the supper of the Lord in our

worship?

To set up the context of the passage, Anthony

Thiselton is extremely helpful.

Thiselton states the following in his preliminary comments of his section on the supper; “their

mode of sharing, or more strictly of failing genuinely to share, the Lord’s

Supper transposed it from being the

Lord’s Supper, which proclaimed his giving of himself ‘for others,’ into

little more than a party meal given for the benefit of some inner group invited

by the host of the house.”[3]

It seems that this paraphrase by

Thiselton sums up the passage the best that I believe it can be summarized within the

context. Paul is instructing the

Corinthians on the basis of problems with the supper’s administration. Having just finished a section on actions he

was pleased to praise them for – their usage of the proper head coverings in

the context of headship – Paul changes the tone in these beginning verses of

the new section. “In the following directives I have no praise for you, your meetings do

more harm than good.”[4] There are many traditional

perspectives on this passage of scripture, but not all of them are helpful in

determining any real or practical application.

We will look at some of the traditional views and specifically how these

passages are strong and weak in light of the cultural context.

Although this passage is the most

complete section of scripture on the topic of the Lord’s Supper, Paul is by no

means exhaustive in the supper's background of observance in the church. Paul also doesn't seem to ever change cultural customs in any city in his ministry if the cultural practices do not violate Christian principles. He does not relate to

the reader the origins of theology for the supper, but his instruction “is a narrow, focused response to a

specific problem in the Corinthian church.”[5]

Gordon Fee identifies the real problems in this

passage as both horizontal and vertical relationships that are

violated. Fee states that the real issue of this passage is not the

drunkenness that takes place at the table of the Lord, or the cultural

distinctions per se, but the abuse of the church itself.[6] We must understand that with all of the

problems of the Corinthian church, the problems with the Lord’s Supper are only

symptoms of the greater issue of social and spiritual injustice that had already resulted from prior status issues and prejudices. The Corinthians were segmented, split, lined up with party positions and cliques, and had the typical Greek attitudes toward wisdom (sophism) and philosophy that naturally gave an air of haughtiness and self-centeredness to the individual taken by it. Thus, a disregard for the needs or poor people and slaves is no surprise to any reader that places himself back in the cultural context of the local church at Corinth; perhaps even the church meeting in the house of Gaius (Rom. 16:23 - with Gaius and Erastus, a prominently known Corinthian treasurer).

A COMMON MEAL of the Lord's Supper?

There can be no doubt that the

Christians were partaking of the supper of the Lord in the setting of the

common meal, otherwise known as the Agape love feast. Archaeology and literature both testify strongly of this

practice, specifically helpful are the writings of the church fathers on the

supper of the Lord (for more on this topic, see Everett Ferguson, "Early Christians Speak" for numerous accounts of the history of this practice). While this paper is

not designed to thoroughly explore the setting of the love feast, a basic

understanding of it is helpful in contemplating Paul’s instruction to

Corinth. According to Ben Witherington,

the supper of the Lord in Corinth was apparently meant to be more like the Saturnalia, which was a meal designed in

the Greco-Roman context to be more democratic than typical social feasts,

therefore catering to the poor at the meal.[7]

The supper in the Corinthian church

would have been almost nothing that we would recognize today. Our assemblies are so formal compared to the

practices of the supper in that context, our culture would no doubt be

uncomfortable with the combination of the various aspects of the meal and

supper. As mentioned above, Thiselton

alluded to the irony of the church gatherings.

Although the suppertime was designed to pull them together, the supper

was actually driving them apart. So it must be understood that in THAT Roman/Corinthian context, the combination of the meal and the memorial to the Savior combined the current customs with ethical relationships between brothers and sisters in Christ. Therefore, Paul's instruction begins to take on a different meaning when we look at this passage in light of the Greco-Roman culture that these ex-pagans still found themselves living in.

An important factor that must be mentioned again; any reader must keep in mind that Paul did not try and change individual churches’

background customs if they did not violate Christian principles. If that were Paul's purpose, why not change all the Jews' observance of Torah practices that they were still carrying over into their Christianity? Why not have a universal code of Christianity that regulated every daily practice and custom of every day and time that any Christian may subsequently live in? Surely Paul as an Apostle of the Lord knew that different cultures and different parts of the world (certainly different periods of time) have differing practices (see 1 Cor. 9:19-23 and many other NT passages - Paul's discussion of changing his personal practices to "do all things for the sake of the gospel). The customs of the supper’s setting in Corinth

were established traditions. Even

earlier than the 50’s A.D., Socrates wrote instructions about the

administration of such a feast in the social setting, apart from religious

observance; that the poor guests are not humiliated by the fact that they could

bring nothing to the meal.[8] Here Paul is trying to stop abuse from

occurring at the table of the Lord, which is to be sanctified. Paul’s correction takes a turn of sarcasm

with verse 19 of the text.

So what were

the customs?

Virtually every writer on this topic describes the dining

customs of this period, and Thiselton does well to explain the actual setting

of the meal in the common Grecian villa.

“It is quite clear that when more than nine or ten people came to

dinner, the poorer or less esteemed guests would be accorded space not in the

already occupied triclinium, but in

the scarcely furnished atrium, which functioned in effect as an ‘overflow’ for

those who were, in the eyes of the host, lucky to be included at all.”[9] A triclinium was a room that was reserved

for the special guests of any dinner or household festival. Referred to as a triclinium, the three-sided

lounging area around the dinner table would be made of stone, and resembled a

square with one side missing. This

setting facilitated the status distinctions in Corinth.

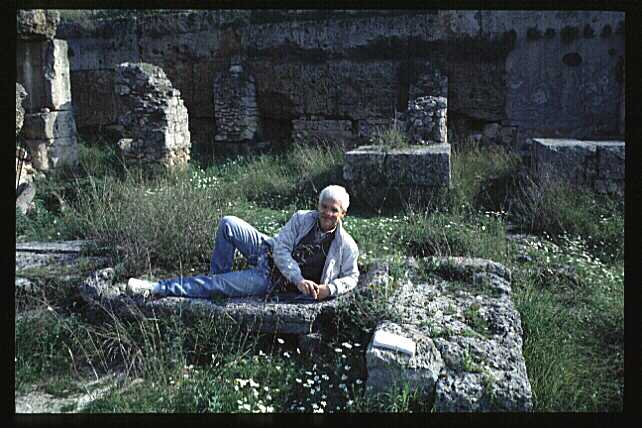

A Roman Triclinium such as the ones found at

Corinth

A triclinium in a villa in "present day" ancient Corinth

(one of my

classmates from Harding Graduate School)

Thiselton goes on to describe a writing by Pliny

the Younger delineating between the categories of food and drink distinction,

relative to the grade of guests in each place.

Richard B. Hays also gives this description by Pliny; “…One lot was

intended for himself (the host - DE) and us, another for his lesser friends

(all his friends are graded), and the third for his and our freedmen.[10] Surely these cultural practices would not

have pervaded the church! But Paul

shows that they have, and in verse 20-21 states the root of the problem.

Several interesting comments by

different writers are helpful in understanding Paul’s transition in these two

verses. In shocking contrast to the

name of the memorial feast that they are partaking, Paul says that the

Corinthians are not eating the Lord’s supper, but they are actually

participating in only a common meal,

not unlike their normal meals with distinctions in status. In doing this, they are “despising the

church of God and refusing those who have nothing.” Richard Oster’s comments are also insightful on this section of

verses. Oster states that the problem

here is not with the participants of the supper or the officials of the meal,

nor is it a “predetermined liturgical pattern” that has been violated. But in fact the specific problem is that

this meal “that is supposed to engender and reflect corporate unity (10:17-17)

has become completely individualistic.

If it were a true supper of the Lord the participants would partake in a

way that manifested their fellowship in the body of Christ.”[11]

The ownership and administration of

this feast is to be that of the Lord’s supper, or kuriakon deipnon (supper to the Lord - literally), not their own selfish celebrations

or manipulation and perversion of their Christian identity.[12] The specific problem of this context is in

verse 21, “for in your eating each one takes his own supper first; and one is

hungry and another is drunk.” This

passage shows grave importance in the application of the supper that the Corinthians

were violating. While this

memorial was taken in conjunction with the meal, (referred to in later periods

as the Agape) it is in no way exemplifying any sort of love feast in Corinth.

Considering the instruction that Paul makes here, it is apparent

that the portions were greater than the portions of the bread and cup that we serve today in our

churches.

Those who were feasting ahead of the others in verse 21

are shaming the poor; this may be one reason Paul says to "wait for one another." They were causing

those who were poor to have personal shame because of their lack of financial

promise or social standing in any particular way; which in pagan cultures of ancient the ancient Roman empire had powerful connotations. Robert Jewett points out that

culturally in Corinth, the 'have nots' felt shame as anyone else would today for many reasons; “shame is felt when others demean us on prejudicial grounds, not

because of what we have done but because of our identity… the most damaging

form of shame is internalizing such evaluations, which imply that we are

worthless, that our lives are without significance.”[13] That is precisely what occurred between the

rich and poor Christians; the rich were perpetuating their social divisions

(even in Christianity!) and disregarding their brothers who “have not.”

The poor Christians come to church and culturally

the Lord’s supper must be the highlight of their week. This is the one place where they don’t have to feel

humiliated because they are poor, or homeless, or socially unacceptable; it's the Lord's body! The table of the Lord is to elevate they who are poor and

lower those who are rich, those who are high, and those who are mighty socially in the table sharing of the body and blood of

the Lord. This attitude is consistent with the Christian unity that should be

demonstrated in “discerning the body.”

There have been many traditional

interpretations of verse 22. Paul is

expressing outrage with his comments to the Corinthians in this verse. One traditional opinion of this passage is

this: that Paul is “not only condemning the refusal of the rich to share with

the poor, he is forbidding altogether the practice of eating a common meal at

the public assembly. This verse prohibits

the perverting of the congregational assembly into an occasion for a common

meal.”[14]

Jimmy Allen’s notes on this verse 22

are more accurately supportive of the context, when he reminds the reader that the sin is in

the abuse of the supper and not in the location of the eating of it.[15] His response is primarily to those who would

oppose eating food in the church meeting place, and thereby distort the meaning

of Paul’s instruction to the Corinthians.

Timothy Coyle goes so far as to state, “there is no authority in

scripture for partaking of the eucharist apart from the meal.”[16] Whether his reasoning is entirely accurate or not, this is certainly an interesting point

considering our complete separation from a physical meal in the Lord’s supper

today.

The most probable meaning of verse

22 is what Richard B. Hays says, “He does not deny the right of the more

prosperous Corinthians to eat and drink however they like in their own homes,

but he insists that the church’s common meal should symbolize the unity of the

community through equitable sharing of food at the meal.”[17]

The earliest recent statement of

this position was by Hultreich Zwingli of Switzerland in the 16th

Century.[18] But Paul’s concern here in verse 21 for the

poor is also demonstrated in the discussions of chapters 12-14.[19] These thoughts are also put into words very

eloquently by C.K. Barrett; “The rich man’s actions are not controlled by love;

they therefore amount to contempt not only of the poor, but also of God, who

has called into his church not many wise, not many mighty, not many noble born

(1:26). God has accepted the poor man,

as he has accepted the man who is weak in faith and conscience (8:9-13;

10:29ff); the stronger (whether in resources or faith) must accept him

too. It is by failure here that the

Corinthians profane the sacramental aspect of the supper – not by liturgical

error or by undervaluing it, but by prefixing it to an unbrotherly act.”[20]

One thing that we must admit when

looking at this passage within the context; Paul is not condemning the

partaking of the supper in the form of a meal.

Rather, he is condemning the attitude of the church toward the lesser

members who are being persecuted. In

every church, even today, there are members that may not be financially

blessed, and they are by all means the ones who need the most inclusion in the

blessings of the fold of God. Jesus

stated this with his actions when he repeatedly went to the poor, rather than

the rich, to teach about the kingdom of God.

One observance made by Jeffrey Gibbs is that the

church was “letting the culture dictate” their practice within the church.[21] It is always a dangerous and fragile mix to

implement cultural practices into the church activities. The culture anyone is a part of does not

dictate Christian doctrine. However, it

is also equally dangerous to allow a practice of the early church that was so meaningful and vibrant to become rote

and meaningless in our day by repitition and empty formality.

How could something so successfully celebrated for

the first years be the subject of such abuse in the later years and more

worldly cultures? Many churches today

go through the motions of a couple of prayers, then the passing out of trays

with a wafer and a small sip of juice without really contemplating what the

memorial could be if we allowed the Corinthian instruction to influence our

worship practices.

Another important thing to

understand about the Corinthian context is that the Christians were meeting in

house churches. Typically, every church for the first century and a half was

meeting or had met in a house church.

If in a home the host presided over regular meals, there is no surprise

that the regular practices of meal celebration would carry over into

the Lord’s supper. Gordon Fee rightly

comments that the force of Paul’s direction is on the members’

self-centeredness. “Each enjoys his

‘own supper’ instead of the Lord’s Supper.”[22]

G.C. Nicholson makes a great point

when he observes that Paul’s “injunction” in 11:22 & 34 is a “call to feed

the hungry Christians in the house where the community gathers, rather than as

a command to the ‘haves’ to eat their lavish meals within their own four

walls.”[23] And also Paul is not arguing “against the

Lord’s Supper being a common meal with real food, but to point out that it had

degenerated into a private meal with no food for the majority of the group”

which shows a total disregard for the needs of others.[24]

One of the popular forms of theology

in our modern day is Liberation Theology,

which has many flaws it seems; but Liberation Theology does focus on the needs

of the poor in many practical cases, rather than allowing most of the world’s

typical overlooking of the poor man’s needs.

This is very popular in Catholic Central America, where poverty is

rampant and the needs of the poor are always great. Some scholars have linked the partaking of the supper to our

surrender with Christ, as if we are martyred with him as we partake. In this remembrance of Christ’s death, all

that partake are martyred anew, and brought to a spiritual feast in which they

are replenished beyond measure.[25] In short, William Cavanaugh says that the

Lord’s Supper can bring judgement on a person if they do not “attend to those

who suffer.”[26] Whether our focus with the gospel should

“primarily” be toward the poor or not, the emphasis in Paul’s instruction of

11:17-34 is directed toward equality of all the members. Especially those who have – toward those who

do not have; this is the essence of Christianity!

One of the most intriguing points

made by any of the commentators that I have read is that neither this passage nor the

previous chapter is directly dealing

with the Lord’s Supper.[27] The passages have always been the first

place turned to in the New Testament to reflect on the Lord’s supper, but the

texts do not address the specific positive aspects of the Supper. These texts are very specifically dealing

with the abuses of the supper, caused by selfishness and arrogance, which

incidentally was the cause of nearly every other Corinthian problem. So this is not a specific Lord’s Supper

problem, but a human Christian affairs issue.

Bradley Blue makes an excellent

point as well about the nature of the church when gathered together. He says, “Paul’s emphasis is on defining

what is appropriate and inappropriate when the various house churches gather in

one house: behavior which may be acceptable in the house is not appropriate for

the ‘church’ when gathered in the house.”[28] Romans 16:23 demonstrates the relationship

that should exist in the church (house church) with the example of Gaius’

hospitality. To contrast the example of

Gaius in Romans 16, Luise Schottroff says that the “better off in Corinth have

behaved exactly like Ananias and Sapphira: they have treated common property,

consecrated to God, as if it were private property.[29]

The

Institution of the Supper

Paul now makes the transition into the institution

of the Supper itself as the inspiration for his teaching the character they

should be demonstrating. Thiselton

makes a good case for the institution of the supper being made during the

Passover meal. There is controversy

over the date of the last supper; was it the Passover meal or simply a meal preparing

for the Passover? Thiselton adequately covers this controversy with the dating

systems of the different calendars and the questions about Synoptic gospel

tradition.[30] Jesus did, after all view himself as the

lamb of the Passover in John 1 when he met John the Baptist.

Thiselton does a masterful work when he describes

the connection between Jesus statement to the Apostles, “This is my body,” and

the context of the Jewish Haggadah. “In the Haggadah the person who presides

explains the various elements, objects, and events which fulfill a redemptive

role in the history of God’s people, beginning “a wandering Aramean was my

father…”[31] Thiselton’s information comes from the

research of E. Ruckstuhl, who makes a clear connection to the motive of Jesus

and practical administration as the server and host of the Lord’s Supper. He is, of course, the Lord (kurios) in the Lord’s

Supper (kuriakon deipnon). According to Thiselton, the “details are

immaterial… (whether the meal was the meal of the Passover or not) Jesus

did host the supper, and he was the Passover lamb that proclaimed his broken

body for the “blood of the new covenant.”[32] He continues in surmising that the

replacement in the language of the Haggadah is now that “my body” is the object of remembrance, not the exodus from Egypt or

the wanderings of their father Abraham from the Fertile Crescent.

Paul mentions that the Lord gave

thanks for the bread, broke it, and the Apostles ate the supper with him. The interesting thing, as Everett Ferguson

notes, is that this meal of preparation and celebration of the New Passover was

certainly a part of a meal. Before the

cup is distributed, Paul says, “In the same way He

took the cup also, after supper” which gives us a strong visualization of the

feast eaten together with the Lord.[33] Eugene LaVerdiere adds that as Paul

instructed them about the cup, that they “drink the cup as He drank it, making

clear that it is His memorial.”[34]

In the prior

chapter, Paul uses the illustration of “one bread” to demonstrate that the

members are of “one body” and they are participating in one body

(10:14-17). After a brief segway to the

instruction on headship, Paul is now back to the Lord’s Supper, and is no doubt

using a fresh appeal to the unity of the disciples. For the Christians to participate in any sort of unity with

Christ, there must first be unity amongst themselves.[35] In addition, as the believers participate

together in a unified celebration, they drink the cup of the meal “in

remembrance of Jesus whose life and ministry culminated in his redemptive

death.”[36]

The life, death, and ministry of the Lord Jesus is

the reason for the celebration of such a feast. How can true believers NOT celebrate the sacrificial death of their emancipator from their lives of sin and corruption. As Gordon Fee states, “the focus of Paul’s concern is on this

meal as a means of proclaiming Christ’s death, a point the Corinthians’ action

is obviously bypassing.”[37] At the same time, remembering Christ in his

redemptive role as our Passover has definite ethical implications. Anthony Thiselton reasons this way in

regards to “remembering,” that to “remember God’s mighty acts” or to think

about them with some sort of fond recollection is not the purpose or

remembrance the Lords desires. To

remember Egypt and the exodus from such oppression meant that the people were

to put into their actions certain things that they knew they should do.

Deuteronomy 8:18-19 states this about

remembering; “But you shall remember

the LORD your God, for it is He who is giving you power to make wealth, that He

may confirm His covenant which He swore to your fathers, as it is this day. And

it shall come about if you ever forget the LORD your God, and go after other

gods and serve them and worship them, I testify against you today that you shall

surely perish.” “To ‘remember’ the poor

is to relieve their needs.”[38] Thiselton continues in saying, “the collapse

of this Christian identity undermines what it is to share in my body in such remembrance.”[39]

Another aspect of

great importance in considering the last supper is the setting of that supper and those who were

present that night, "the night of his betrayal." The Apostles were

fishermen, tax collectors, and Zealots.

They were regular folks that were full of sin like any other human would

be. An excellent observation has been

made by Craig Koester that, “Early Christians found the betrayal of Jesus to be

one of the most disturbing aspects of the passion because the perpetrator was

one of Jesus’ intimates, Judas Iscariot.

Yet it was precisely ‘on the night when he was betrayed; that Jesus

‘took bread,’ ‘gave thanks,’ and ‘broke it.’”

He continues that the real relief

of the passage for all Christians should be Jesus’ words that followed, “this

is my body which is for you…”

Recognizing this sin in Jesus’ closest friends is an incredible relief to the

rest of the world because it shows we can actually be forgiven![40] That Jesus would have known that his

betrayer was in the room and at the table with him, yet given him bread (this

is for you and your sins) is incomprehensible. What amazing grace! What unbelievable self-control and maturity displayed by our Lord as the host of his own memorial supper. There is nothing quite so disappointing to a host as an ungrateful guest. Yet, not only was Judas Iscariot an ungrateful guest, he was an intimate brother to the Lord who handed over the king of all earth to the executioners for a mere 30 pieces of silver. What guilt and shame must have overcome Judas to cause his suicide. Yet Jesus still handed the bread to him and said "when you do this, remember me."

Paul continues

discussing the manner in which a person was to partake of the supper. To take the supper meant that one had to

take of it in a worthy manner. What was

a worthy manner? There are several

interpretations of this worthiness; Ferguson makes a good point in saying, “no

one is worthy of God’s grace; that’s why it is grace. No one is worthy of what God has done in Christ, and likewise no

one is worthy of the Lord’s supper or any other spiritual activity. One comes to the table because he is

spiritually needy.”[41]

James Custer

makes a prudent observation as well, in stating that communion does not occur

unless the actions are performed in knowledge of what is symbolized. “Mechanical, thoughtless participation, even

in the “proper” activities, does not create communion.”[42] An example of this has already been seen in

F. LaGard Smith’s recent communion experience earlier in this essay. Custer

continues in saying specifically that in his estimation, eating and drinking

unworthily is a failure to discern the body of believers.[43]

What is

“discerning the body rightly?”

What then is the

body in verse 29? Paul continues his

emphasis that the body must be recognized properly for one to participate

without calling judgment on him. Gordon

Fee states that there are three options for interpreting “body” in verse 29. First, “not recognizing the body” could mean

failure to distinguish the Lord’s Supper food from the common food of their

private meals. Second, the Corinthians

are failing to recognize the Lord’s physical body; that is, to reflect on his

death, as they eat. Third, the meaning

could be a failure to recognize the body of the Lord as the body of the church,

since the church is the body of Christ.

Fee acknowledges

the word plays that Paul uses that are in the theme of “judgment.” Identifying the root verb (diakrinon)

“discerning,” or “recognizing,” Fee states that “the Lord’s Supper is not just

any meal; it is the meal” in which

all diversity of believers is knit together.

To abuse our own body, one part of the body against another, is to incur

God’s judgment.[44]

Thiselton also notes the theme of

judgment when he quotes Collins’ observation:

“Verses 27-32 are replete with judicial language:

‘unworthily…answerable…scrutinize…judgment…chastise…condemn,’ all belong to the

semantic domain of the law and the courtroom.”[45] Judgment is certain when one partakes of

such a memorial in a profane way, without truly discerning the body.

So what does it really mean to discern the body? Even if we agree that discerning the body is to reflect on our brothers and sisters in our local church family, what does that entail? It seems that at Corinth, what is meant is simply to regard the body as a part of the holy extended body that belongs to Jesus himself; to elevate all members of the body to a position of special uniqueness and community fellowship and sharing. Stephen Barton offers

three suggestions, of which the most likely seems to be the church. He identifies the different objects of the

word “body” as the body of the individual, the ecclesial body, and the body of

Christ.[46] John Mark Hicks identifies the language of

the Lord’s supper narratives as the decisive factor in determining the

meaning. Beginning in chapter 10, Paul

uses “body and blood” any time he is referring to the supper. When he mentions body by itself in 10:17, he

is referring to the church community within itself.[47]

In chapter 11,

there are seven occurrences of both “body and blood,” “eats and drinks,” or

“bread and cup” prior to verse 29. Here

in verse 29, for the first time the passage mentions only the body of the

Lord, and all indications appear to refer to the church itself, not the

physical body of Jesus. The Greek text

literally says, “not judging (or recognizing, or discerning, or distinguishing

with judgment) the body.” (mh diakriwn to swma)

One objection to

this position is made by A. Andrew Das, who states “the Apostle’s failure to

mention the blood in verse 29 is probably stylistic and nothing more. He had used ‘body and blood’ already and did

not want to bore his readers with wooden repetitions.”[48] This reasoning does not appear to be correct

in light of the repetition that Paul already uses; if it was, why would he have become

leery of vain repetition this late in the chapter and not before the seventh

occurrence?

Hans Conzelmann

remarks, “it is eating unfittingly when the Supper of the Lord is treated as

one’s ‘own supper.’ Then one becomes

‘guilty’ inasmuch as the man who celebrates unfittingly sets himself alongside

those who kill the Lord instead of proclaiming his death.”[49] To be guilty of the blood of someone is most

naturally understood as meaning ‘to be responsible for the death of someone.”[50]

Paul continues after this section

with the explanation that the reason many are weak and sick are because of this

“not discerning the body rightly.” Is

this some sort of spiritual sickness as punishment, or could it literally be

true? That some of the poor or less

fortunate were neglected to the point of sickness and even death seems to fit

the context from a literal perspective also.

Whether this is a

physical or spiritual sickness and death, the point is well taken, that the

ones who partake of the supper of the Lord must keep their minds and actions on

the correct things.

Hicks gave a

three-fold summary of Paul’s instruction on the topic of the Lord’s

supper. In Paul’s continued instruction

of the Corinthians, he gives these three instructions that must be followed: first, wait till everyone arrives before you

eat the supper. Second, if you are

hungry, eat something at home before you assemble so you can wait for everyone

to arrive. Third, Paul will settle

everything else when he arrives.[51]

This passage is

not only about the Lord’s supper, it is about the ethical treatment of each man

toward his brother at Corinth. Once we

take into account the cultural and spiritual setting of this Corinthian church,

it becomes clearer why we often abuse the memorial and brush the Lord’s supper

under the rug for the sake of time. We

often refer to it as one of the “five acts of worship,” when in actuality it IS

the worship. Our brother’s well being,

health, and self-worth as a Christian are imperative to bring across to the

poor man who is in our midst.

In practical

application, there are many ways we can attempt to restore the New Testament

ideal without changing everything about our worship. However, do the changes need to be made to emphasize the proper

things? Can we reacquire the true meaning

of Communion? “The underlying aim…is

not naively to call for a return to New Testament practice, as if it were

possible to ignore the profound changes experienced during the last 2000 years…[52]

I believe that this is the context in which the supper was abused in the Corinthian church. Without a doubt this meal would be worthy of restoration in our churches. The puzzling thing remains, how do we administer the supper today with the ideal focus of the first century? The church seemed to be an outward focused group in their daily activities, however in their worship seemed to be a completely inwardly focused group. Who knows, we might even achieve equality

and true Christ-like character in our congregations if we gave ourselves up and

looked out for the interests of our need brothers. Can this attitude of Christ-likeness be obtained without a present-day

reinstitution of the supper of the Lord?